On the Road

| On the Road | |

|---|---|

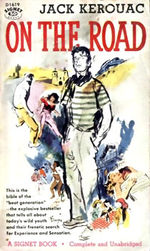

On the Road. Signet first printing, 1958. |

|

| Author | Jack Kerouac |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Novel Beat |

| Publisher | Viking Press |

| Publication date | September 5, 1957 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 320 pages |

| ISBN | 978-0-141-18267-4 |

| OCLC Number | 43419454 |

| Preceded by | The Town and the City (1950) |

| Followed by | The Subterraneans (1958) |

On the Road is a novel by American writer Jack Kerouac, written in April 1951, and published by Viking Press in 1957. It is a largely autobiographical work that was based on the spontaneous road trips of Kerouac and his friends across mid-century America. It is often considered a defining work of the postwar Beat Generation that was inspired by jazz, poetry, and drug experiences. While many of the names and details of Kerouac's experiences are changed for the novel, hundreds of references in On the Road have real-world counterparts.

When the book was originally released, The New York Times hailed it as "the most beautifully executed, the clearest and most important utterance" of Kerouac's generation.[1] The novel was chosen by Time magazine as one of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to 2005.[2]

Contents |

Origins

A popular legend is that On the Road was written in three weeks while Kerouac lived with Joan Haverty, his second wife, at 454 West 20th Street in Manhattan, New York, is apocryphal. It took nine years for the final copy to be published. Kerouac typed the manuscript on what he called "the scroll":[3] a continuous, one hundred and twenty-foot scroll of tracing paper sheets that he cut to size and taped together. The roll was typed single-spaced, without margins or paragraph breaks. Contrary to rumors, Kerouac said he used no stimulants during the brief but productive writing session, other than coffee.[4] Plans to publish the original scroll were announced in 2006;[5] Viking Press published On the Road: The Original Scroll in 2007.[4]

In 2007, it was discovered that Kerouac first started writing On The Road in French, a language in which he also wrote two unpublished novels.[6] These writings are in dialectal Quebec French, and predate by a decade the first novels of Michel Tremblay.

"The scroll" still exists — it was bought in 2001, by Jim Irsay (Indianapolis Colts football team owner), for $2.43 million, and is available for public viewing. The scroll was displayed in sections at Indiana University's Lilly Library in mid-2003, and in January 2004, the roll started a thirteen-stop, four-year national tour of museums and libraries, starting at the Orange County History Center in Orlando, Florida. From January through March 2006, it was at the San Francisco Public Library with the first 30 feet (9 m) unrolled. It spent three months at the New York Public Library in 2007, and in the spring of 2008 visited the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The scroll traveled next to Columbia College Chicago in the autumn of 2008, then was displayed at the Birmingham University in the United Kingdom, before being moved once more to University College, Dublin, Ireland and then to National University of Ireland, Maynooth before returning to the US in March 2009.

The legend of how Kerouac wrote On The Road excludes the tedious organization and preparation preceding the creative explosion. Kerouac carried small notebooks, in which much of the text was written as the eventful seven-year span of road trips unfurled. He furthermore revised the scroll's text several times before Malcolm Cowley, of Viking Press, agreed to publish it. Besides the differences in formatting, the original scroll manuscript contained real names and was longer than the published novel. Kerouac deleted sections (including some sexual depictions deemed pornographic in 1957) and added smaller literary passages.[7] Viking Press released a slightly edited version of the original manuscript on 16 August 2007 titled On the Road: The Original Scroll corresponding with the 50th anniversary of original publication. This version has been transcribed and edited by English academic and novelist, Dr. Howard Cunnell. As well as containing material that was excised from the original draft due to its explicit nature, the scroll version also uses the real names of the protagonists, so Dean Moriarty becomes Neal Cassady and Carlo Marx becomes Allen Ginsberg etc.[8]

Character key

"Because of the objections of my early publishers I was not allowed to use the same person's name in each work." [9]

| Real-life person[10] | Character name |

|---|---|

| Jack Kerouac | Sal Paradise |

| Gabrielle Kerouac | Sal's Aunt |

| Alan Ansen | Rollo Greb |

| William S. Burroughs | Old Bull Lee |

| Joan Vollmer | Jane |

| Lucien Carr | Damion |

| Neal Cassady | Dean Moriarty |

| Carolyn Cassady | Camille |

| Hal Chase | Chad King |

| Henri Cru | Remi Boncoeur |

| Bea Franko | Terry |

| Allen Ginsberg | Carlo Marx |

| Diana Hansen | Inez |

| Alan Harrington | Hal Hingham |

| Joan Haverty | Laura |

| Luanne Henderson | Mary Lou |

| Al Hinkle | Ed Dunkel |

| Helen Hinkle | Galatea Dunkel |

| Jim Holmes | Tom Snark |

| John Clellon Holmes | Tom Saybrook |

| Herbert Huncke | Elmer Hassel |

| Frank Jeffries | Stan Shephard |

| Gene Pippin | Gene Dexter |

| Ed Stringham | Tom Saybrook |

| Allan Temko | Roland Major |

| Bill Tomson | Roy Johnson |

| Helen Tomson | Dorothy Johnson |

| Ed Uhl | Ed Wall |

Plot summary

The book begins by introducing the catalyst for most of the adventures of the story: Dean Moriarty (Neal Cassady). The narrator, Salvatore “Sal” Paradise (Kerouac), is fascinated with the idea of humanity, and particularly his eclectic group of friends, jazz, the landscapes of the United States, and women. The opening paragraph states that "with the coming of Dean Moriarty began the part of my life you could call my life on the road."

Soon after Dean arrives in New York City, New York, he meets Carlo Marx (Allen Ginsberg), Sal’s closest friend in the city. Sal tells us that a “tremendous thing happened," and that the meeting of Dean and Carlo was a meeting between “the holy con-man with the shining mind [Dean], and the sorrowful poetic con-man with the dark mind that is Carlo Marx." Carlo and Dean share stories about their friends and adventures around the country. Sal describes his fascination with these two men, and others he will meet along the road, as being part of his overall interest in otherworldly characters.

In July 1947, Sal is ready to begin his first foray across the continent towards the West Coast. His friend Remi Boncœur (Henri Cru) has sent an invitation to join him, with hints of worldwide travels aboard a ship. He sets out with fifty dollars in his pocket.

Sal journeys to Chicago, Illinois. He dates the narrative at 1947, marking it as a specific era in jazz history, “somewhere between its Charlie Parker Ornithology period and another period that began with Miles Davis,” and it inspires Sal to think of his friends “from one end of the country to the other…doing something so frantic and rushing about.”

In San Francisco, California, Sal takes a job as a night watchman at a boarding camp for merchant sailors waiting for their ship. Sal’s aversion to commitment and duty ensure that he does not hold this job for long, and he is soon on the road again, where he meets one of his biggest temptations.

Her name is Terry, and he meets her on the bus to Los Angeles, California. She is Mexican, and has run away from her husband. They spend “the next fifteen days…together for better or for worse.” Sal spends the better part of a week with Terry and her family in a migrant worker’s camp. The agrarian lifestyle initially appeals to Sal, and he says that he “thought [he] had found [his] life’s work.” Then economic reality sets in and Sal begins to pray “to God for a better break in life and a better chance to do something for the little people [he] loved.”

Sal’s continued journey on the road is entwined with the making of Dean as the epic hero: Dean Moriarty, the “son of a wino”. Dean has spent time in prison, for stealing cars. Dean’s imprisonment, according to Sal, is when his heroic personality was solidified. Prison had the effect of fueling his obsession with the road. What makes him heroic to Sal is his free nature, and his reluctance to tie his spirit to social demands. The decline of Dean makes up the second part of the novel, and culminates in the end of Sal’s journeys.

Sal’s travels erode into disappointment. He slowly becomes more dissatisfied with what he finds on the road, and he begins to look back on his previous travels in a more cynical way. His companions begin to be people from lower classes, old African-American men and Mexican prostitutes. Back in Denver, Colorado, and very alone, he speaks in verse, saying “Down in Denver, down in Denver/All I did was die.” We begin to confront the possibility that this journey and Sal’s hero Dean were both failures.

After reuniting with Dean, Sal begins to sense Dean’s decline and labels him “the HOLY GOOF”, when earlier he was called holy in a reverent tone. Dean’s abilities falter. When confronted with his abandonment of wife and child, he is silent. Sal explains, “where once Dean would have talked his way out, he now fell silent.... He was BEAT.”

Sal’s last attempt at finding an answer to his problems is a trip through the Mexican countryside to Mexico City with Dean and a hanger-on picked up in Denver. The travellers perk up as soon as they hit the Mexican border, and some of the novel's more memorable scenes depict their marijuana-infused introduction to Mexican culture, including a vivid (but expensive) sojourn to a bordello offering mambo music and underage prostitutes.

Upon arriving in Mexico City, Sal develops dysentery, and Dean leaves him behind, feverish and hallucinating. Sal reflects that “when I got better I realized what a rat he was, but then I had to understand the impossible complexity of his life, how he had to leave me there, sick, to get on with his wives and woes.”

The novel ends a year later in New York City. Dean comes back to New York to see Sal and arrange for Sal and his girlfriend to move to San Francisco with him. The arrangements to move fall through and Dean returns to the West alone.

Sal closes the novel sitting on a pier during sunset, looking west. He reminisces on God, America, crying children, and the idea that "nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old," and ends with “I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty."

Reaction

In his review for The New York Times, Gilbert Millstein wrote, "its publication is a historic occasion in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment in an age in which the attention is fragmented and the sensibilities are blunted by the superlatives of fashion," and praised it as "a major novel."[11] David Dempsey wrote that Kerouac delivered, "great, raw slices of America that give his book a descriptive excitement unmatched since the days of Thomas Wolfe."[12]

Influence

On the Road has been a huge influence on many poets, writers, actors and musicians, including Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, Hunter S. Thompson, and many more. "It changed my life like it changed everyone else's," Dylan would say many years later. Tom Waits, too, acknowledged its influence, hymning Jack and Neal in a song, and calling the Beats "father figures." At least two great American photographers were influenced by Kerouac: Robert Frank, who became his close friend - Kerouac wrote the introduction to The Americans - and Stephen Shore, who set out on an American road trip in the 1970s with Kerouac's book as a guide. It would be hard to imagine Hunter S. Thompson's road novel, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, had On the Road not laid down the template - likewise films such as Easy Rider, Paris, Texas, even Thelma and Louise.[13]

Film adaptation

A film adaptation of On the Road has been in the works for years. Gus Van Sant owned the rights for many years and was going to emphasize the subjective homoerotic undertones in the novel. Russell Banks wrote a screenplay for producer Francis Ford Coppola, who bought the film rights for $95,000 in 1980.[14] The Brazilian director Walter Salles is now heading the project. After seeing Salles's The Motorcycle Diaries, Coppola decided on Salles and the production is underway.[15] In preparation for the film, Salles traveled the United States, tracing Kerouac's journey and filming a documentary on the search for On the Road.[16] Jose Rivera has adapted the book into a screenplay. Coppola's American Zoetrope is producing the film, in association with MK2, Film4 in the U.K. and Videofilmes in Brazil. Sam Riley will star as Kerouac's alter ego Sal Paradise. Garrett Hedlund has been cast as Dean Moriarty.[16] Kristen Stewart has confirmed that she will play Mary Lou.[17] Kirsten Dunst will be playing Camille.[18] Filming has officially begun as of August 02, 2010.[19] Filming will take place in New Orleans, Montreal and Mexico with a $25 million budget.[16][20]

Criticism

Truman Capote famously quipped of the novel: "That's not writing, that's typing."[21] Kerouac scholar Matt Theado points to the book's multi-layered reputation: "Kerouac's most famous novel comes with many associations that work to inform and mislead the reader before the cover is opened. The book is both a story and a cultural event."[22] David Ulin says in Book Forum that "even the most frantic of Kerouac’s writings were really the sagas of a solitary seeker: poor, sad Jack, adrift in a world without mercy when he’d rather be 'safe in Heaven dead.'"[23] "Kerouac was this deep, lonely, melancholy man," said Hilary Holladay at the University of Massachusetts.[23] "And if you read the book closely, you see that sense of loss and sorrow swelling on every page."[23] John Leland, author of Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of On the Road (They're Not What You Think), says "We're no longer shocked by the sex and drugs. The slang is passé and at times corny. Some of the racial sentimentality is appalling" but adds "the tale of passionate friendship and the search for revelation are timeless. These are as elusive and precious in our time as in Sal's, and will be when our grandchildren celebrate the book's hundredth anniversary."[24]

See also

- References in On the Road

- Off the Road

References

- ↑ Millstien, Gillbert. Books of the Times The New York Times Book Review. September 5th, 1957

- ↑ "Time Magazine - ALL-TIME 100 Novels: The Complete List"

- ↑ Gerald Nicosia, his biographer.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sante, Luc. "On The Road Again" New York Times Book Review August 19, 2007

- ↑ Russell, Jenna (2006-07-27). "Kerouac's `Road' will be unrolled". The Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2006/07/27/kerouacs_road_will_be_unrolled/. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Les 50 ans d'On the Road - Kerouac voulait écrire en français

- ↑ Sante, Luc. "On The Road Again" New York Times Book Review August 19, 2007

- ↑ Bignell, Paul (July 29, 2007). "On the Road (uncensored). Discovered: Kerouac "cuts"". The Independent (London). http://arts.independent.co.uk/books/news/article2814743.ece. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Kerouac, Jack. Visions of Cody. London and New York: Penguin Books Ltd. 1993.

- ↑ Sandison, Daivd. Jeck Kerouac: An Illustrated Biography. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. 1999

- ↑ Millstein, Gilbert (September 5, 1957). "Books of the Times". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/09/07/home/kerouac-roadglowing.html. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ↑ Dempsey, David (September 8, 1957). "In Pursuit of 'Kicks'". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/09/07/home/kerouac-roadbr.html. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ↑ O'Hagan, Sean (August 5, 2007). "America's first king of the road". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/aug/05/fiction.jackkerouac. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Maher, Paul Jr. Kerouac: The Definitive Biography. Lanham, Md.: Taylor Trade Publishing, 1994, 317.

- ↑ Soloman, Karen (August 17, 2010). "Hollywood comes to Gatineau to film On the Road". CTV News. http://ottawa.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20100817/OTT_Gat_Movie_100817/20100817/?hub=OttawaHome. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Kemp, Stuart (May 6, 2010). "Kristen Stewart goes On the Road". The Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3i0b2233969ec82f2c19dab6dab58ac895?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+thr/film+%28The+Hollywood+Reporter+-+Film%29&utm_content=Google+Reader. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ "Kristen Stewart to star in Jack Kerouac story". USA Today. May 5, 2010. http://content.usatoday.com/communities/entertainment/post/2010/05/kristen-stewart-to-star-in-jack-kerouac-story/1. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Hopewell, John; Elsa Keslassy (May 12, 2010). "Dunst joins Stewart On the Road". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1118019196.html?categoryid=3628&cs=1&nid=2562&utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+variety%2Fheadlines+%28Variety+-+Latest+News%29&&. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- ↑ "'On the Road' Officially Starts Filming in Montreal". August 2, 2010. http://www.onlocationvacations.com/2010/08/02/on-the-road-officially-starts-filming-in-montreal/. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ↑ Sperling, Nicole (May 6, 2010). "Kristen Stewart squeezes Walter Salles On the Road in between Twilight duties". Entertainment Weekly. http://hollywoodinsider.ew.com/2010/05/06/kristen-stewart-squeezes-walter-salles-on-the-road-in-between-twilight-duties/. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Elmont, Ewin Ritchie (1992-10-25). "What Capote Said About Kerouac". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1992/10/25/nyregion/l-what-capote-said-about-kerouac-670892.html. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ Theado, Matt. Understanding Jack Kerouac. Columbia SC: University of SC Press, 2000.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 The New York Times. "Sal Paradise at 50" by David Brooks. October 2, 2007.

- ↑ Amazon Books. "Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of On the Road (They're Not What You Think)." "Questions for John Leland."

Further reading

- Gifford, Barry & Lee, Lawrence (2005), Jack's Book: An Oral Biography of Jack Kerouac, New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, ISBN 1560257393

- Leland, John (2007), Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of On the Road (They're Not What You Think), New York: Viking Press, ISBN 9780670063253

- Nicosia, Gerald (1994), Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0520085698

External links

- Jack Kerouac characters, Real names and their aliases, alphabetically

- A comprehensive guide to every character in Kerouac's writing, with biographical notes

- The Beat Museum in San Francisco

- A gallery of On the Road book covers

- Denver Beat Photo Tour

- Photos of the Kerouac Gas Station in Longmont, CO

- Photos, Neal Cassady Sr. Gravesite

- Photos, Jack Kerouac's Last House, St. Petersburg, FL

- Google Earth tour of sites visited in "On the Road"

- Photos of the First Edition of On the Road

- An NPR Story about the travelling manuscript

- Tracing Kerouac's tracks through North Platte, Lincoln County and Nebraska North Platte Bulletin Staff - 7/21/2007

- The beat goes on: Tracing Kerouac's tracks 50 years later: A restless spirit and 'holy' pie endure By Charles M. Sennott, Boston Globe Staff, July 15, 2007

- On the Road Book Notes from Literapedia

- On the Road: A book review

- On the Road study guide, themes, quotes, multimedia, teacher resources

- Victoria Mixon's Interviews with Carolyn Cassady

- On the Road on Open Library at the Internet Archive

|

|||||||||||||||||